On my travels outside Taiwan when I meet people and tell them where I spent more than a decade of my life, they sometimes ask what language is spoken in the country. The easiest answer to give, if you’re in a hurry, is “Chinese”. But the truth is much more interesting. Taiwan has a rich and diverse linguistic heritage that makes the place fascinating to anyone with an interest in languages.

When people say “Chinese”, they normally mean Mandarin Chinese. This is the official standard in both China and Taiwan. You might then hear people say that Taiwanese or Shanghainese or Cantonese is a “dialect” of Chinese. This is something that linguists interested in Chinese languages get tired of hearing, because it doesn’t make any sense in context. So what is a dialect? To understand that, we need to understand the concept of mutual intelligibility. Imagine two people together in a room, trying to speak to each other. Neither have had any training in other languages. If one is from London and the other from New York, they will be able to understand each other pretty easily; the differences are small enough. New Yorkish and Londonese are mutually intelligible because they are both dialects of one language: English. If you put an Icelander and a German in the same room, they won’t be able to communicate easily. Even though Icelandic and German are part of the same language family, and share some common roots, they are separate languages. They are mutually unintelligible.

So, what’s the situation with Chinese? Dialects or languages? Well, the major varieties of Chinese are almost completely incomprehensible to a speaker from another variety. So “Chinese” is really a family of languages, like Germanic (which contains English, Dutch, German, Icelandic etc.) or Romance (French, Portuguese, Romanian, Italian and so on). Within this Chinese family, there are a number of languages; some say eight, some nine, some a much larger number. Within these languages there are real dialects, versions of a language that are different, but still mostly comprehensible to each other.

For Taiwan though the story is relatively simple: there are three Chinese languages spoken here. Mandarin Chinese is the official national language, and spoken by almost everyone. The second, Taiwanese, is widely spoken, especially outside Taipei. Meanwhile Hakka, the third variety, is spoken by a distinct group of people (also called Hakka) who live mainly clustered around Hsinchu, Taoyuan County, and a rural area of Kaohsiung.

The Formosan Languages

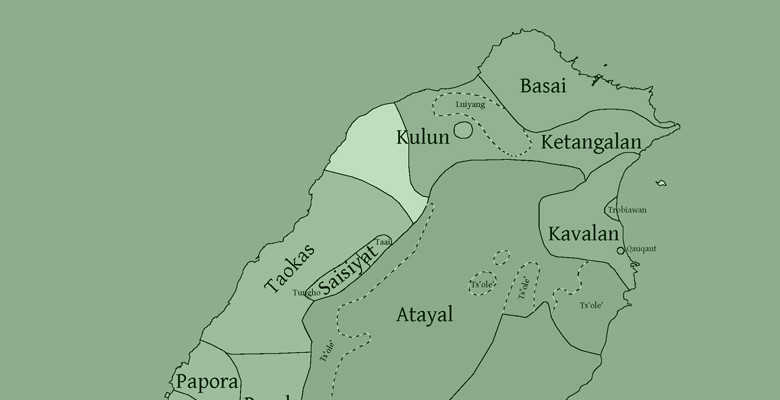

These three account for almost everyone in Taiwan, with a majority of people speaking Mandarin plus another language (usually Taiwanese, occasionally Hakka). But distinct from the Chinese languages is a group of languages spoken by the Aboriginal inhabitants of the island. Genetically, culturally, and linguistically distinct, the Aborigines have been in Taiwan for perhaps 10,000 years while the Han Chinese people only began arriving in large numbers 400 years ago. Today they make up a small minority of the population, and their languages are all under threat. In some cases there are just a handful of aged speakers left, and even the healthiest Formosan languages (as they are called) are in danger of dying out if steps are not taken to encourage younger people to speak them. The strongest of these languages is perhaps Amis, with a fairly large population and an active push through education to ensure the language is not lost. Another language, Siraya, was declared extinct after the assimilation of the tribe into Han Chinese society, but has recently been resurrected by a group of enthusiasts using written records dating from the Dutch era in Taiwan (1624–1662).

Despite the relatively small number of speakers of the Formosan languages, this group has an outsized significance in relation to the Austronesian family, a group of languages spoken over a vast area that stretches from Madagascar in the west to New Zealand in the south, to Hawai’i in the northeast. Malay (Bahasa Melayu), the official language of Indonesia and Malaysia with over 200 million speakers, is an Austronesian language. Comparative linguistics suggests that all of these languages originated in Taiwan, so the tiny communities of Austronesian speakers in Taiwan are of significant interest to linguists. All of this attention, however, will sadly probably not be enough to save these languages from extinction.

Mandarin

The national language, and the one language almost everyone in Taiwan speaks to some degree, Mandarin is a surprisingly recent arrival. Imposed by the KMT government after 1945, students were fined and beaten for speaking anything other than Mandarin in schools up until the 1980s. The efforts to force this foreign “national standard” on the Taiwanese were generally successful, and it’s now unusual to find a person who doesn’t speak to at least a passable level. In writing it has an even more dominant position, with only a few hardcore and rather eccentric people choosing to write in Taiwanese or another local language. Foreign nationals moving to Taiwan and learning a language overwhelmingly opt for Mandarin rather than Taiwanese—and who can blame them? Besides its near-universal utility in Taiwan itself, it’s also the national language of neighbouring China, and one of the five most significant languages in the world (Arabic, English, Russian and Spanish would be the others, in my opinion).

Taiwanese

Sometimes called Minnan, Hokkien, Fujianese, Hoklo, and a few more things besides, Taiwanese is the native language of the Minnan people, a group of Han Chinese who make up around 70% of the population of Taiwan. Throughout much of the island it’s the language of the street, of the market, of home and hearth. It’s the language of friendship, and of fighting. Swearing in Taiwanese is almost universally agreed to be more pungent and satisfying than Mandarin cursing. It has an earthier feel than Mandarin, but can claim a long and aristocratic history both in Taiwan and, in its Minnan cousins, in China.

Matsu, a tiny island group off the coast of China but controlled by Taiwan, is home to a small number of Bang-ua speakers (also called Mindong or Fuzhounese), which is a language more closely related to Taiwanese than Mandarin is, but nevertheless different enough that speakers of Bang-ua and Taiwanese cannot readily understand each other.

Hakka

The Hakka are a clannish group of Han Chinese whose name translates as “guest people”. Long wanderings from their ancestral home in northern China, forced by hostility from other groups, has moulded them into a hardy and self-reliant people. Their language is similarly distinctive, though to the casual listener it can sound a little like Cantonese. Under pressure from Mandarin and with fewer younger Hakka growing up as fluent speakers, some preservation efforts have already started, with the advent of Hakka TV (channel 17, if you want to check it out) and language classes springing up in Hakka areas. While there are still a couple of million speakers left, the future is looking uncertain for Hakka, as it is for all of Taiwan’s minority languages.

Taiwanese Sign Language

There are around 20,000 fluent signers of Taiwanese Sign Language (TSL) in Taiwan, most of who have been through one of the specialist deaf schools on the island. Signers from the different schools have different “accents” in TSL, so a signer from Taipei will be able to tell that another signer is from Tainan by the way they sign some words, as well as a few differences in vocabulary.

The influence of the colonial Japanese government on education in Taiwan from 1895–1945 means that TSL shares some similarities with Japanese Sign Language, but the two are not mutually intelligible. TSL and Chinese Sign Language, the form used in the PRC, are completely different. TSL is also not related to any of the other languages in Taiwan, and uses very different patterns of grammar to the mainstream spoken languages. Aside from TSL, which is a fully developed language in its own right, there is also a system for signing Chinese characters called Signed Mandarin, and unlike TSL this follows the grammar of written Mandarin Chinese exactly.

The Others

Aside from the “native” languages of Taiwan above, there is a whole raft of languages brought in by recent immigration or education. English, with its dominant role as the language of international commerce, is of course widely taught (if not quite so widely learned to a decent standard). Japanese, which was previously taught as the official language during the colonial era, is now considered Taiwan’s second foreign language, after English. There are still a few elderly Taiwanese people who speak Japanese fluently as a result of their schooling.

Taiwan is also home to hundreds of thousands of immigrants from Southeast Asia, particularly Vietnam, Indonesia, Thailand, and the Philippines. The languages of these recent arrivals can be heard throughout the country, and signs in Vietnamese in particular can be seen from time to time above shops and convenience stores.

The diversity of Taiwan’s languages makes the island a wonderful place for the amateur linguist or budding polyglot. As someone who has studied, been frustrated by, and admired some of these languages, I can only encourage you to get out there and experience the delights of talking in Taiwan.